Puget Sound Sage and many of our partners in South Communities Organizing for Racial and Regional Equity (South CORE) have been fighting and pushing for a strong inclusionary zoning policy in the City of Seattle since 2008. We have consistently pushed and a strong inclusionary zoning (IZ) policies in order to share in the benefit of increased land value created through public investment and increases in zoning capacity. For the most part, the City of Seattle has already upzoned downtown, South Lake Union, and many urban villages without getting much in return. But a strong IZ policy for the rest of the city could leverage the next wave of development to ensure our communities can prosper in place.

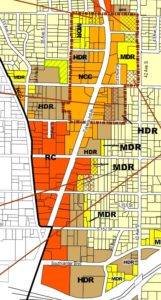

Although we support inclusionary housing and increasing housing supply to accommodate the growth of our region in principle, Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) in its current form, may cause more harm than good in specific neighborhoods. The low affordable housing/in-lieu fee required of developers will not adequately slow increasingly speculative land values in many neighborhoods, especially places that have been designated as high displacement risk. (These are neighborhoods that are at risk largely because of historic systems of institutional racism in housing and job markets.) In the current real estate market, any increased zoning capacity creates a tipping point for both price and speed of land sales, with purchase prices well over asking and appraised values. Local buyers, especially non-profit developers and community based groups, cannot compete in this kind of market, removing the most effective tool against displacement—community-driven and controlled development.

While MHA will hopefully create 6,000 new units of affordable housing over the next 10 years, easing the overall affordability crisis, it does little to address displacement in specific neighborhoods which are most at risk. MHA will help reduce the impacts of the affordable housing crisis for the future residents of Seattle, but the policy does nothing to prevent impending displacement and eventual houselessness of currently housed low-income communities and communities of color.

We believe the time to be bold is now. Over the years, Sage has consistently argued for a strong inclusionary zoning policy with specific anti-displacement focus, based on a racial justice analysis. Unfortunately, we get same message from a majority on Council and the Mayor’s office: if the policy “goes too far” we will get sued by developers, potentially resulting in state pre-emption or legal precedent that undermines any inclusionary policy. But there are many examples when Council has adopted legislation with known risks of litigation, including the First in Time policy, for-hire driver collective bargaining ordinance, and progressive income tax. The difference has been who is group threatening to sue – developers seem to always force the City into watering down legislation and not taking risks. The inconsistent application of this argument isn’t really about legal precedent or pre-emption in the case of MHA, but rather reveals who wields power in City Hall and ultimately determines the fate of communities of color and low-income people in our City.

Among 65 recommendations in HALA, one specifically calls for a comprehensive anti-displacement strategy. Since HALA, advocates have shaped and won important strategies like the Equitable Development Implementation Plan and subsequent Fund, but we still lack adequate funding source for the EDI to stem the tide of displacement. Additionally, existing policies and funds need to re-orient to complement and center the EDI support community-driven development. If we believe that self-determination is a core value of social and racial justice, we need MHA and all City policies to focus on helping marginalized communities thrive in place. So, alongside implementation of MHA through the citywide rezone, we need the City to create and adopt a comprehensive anti-displacement work plan.

We believe that housing is a human right, that low-income communities and communities of color have a right to self-determination, and that development without displacement is possible through community stewardship of land. MHA does not deliver on these values, which is why we support the following set of strategies that can make MHA better and compliment the City’s inclusionary housing strategy.

We urge the City to:

1. Re-evaluate the MHA percent designation for neighborhoods with high displacement risk. Just over the last year, land values have skyrocketed in neighborhoods with high displacement risk and low and medium cost neighborhood designations should be revised to match the rising cost of land.

2. At a minimum, direct in-lieu fees generated from neighborhoods with high displacement risk back to those neighborhoods as investments in affordable housing and community-driven anti-displacement projects.

3. Determine a permanent and adequate funding source for the Equitable Development Initiative beyond the $5 million per year brought in by the tax on short-term rentals. When the current real-estate cycle eventually slows, that fund will become even more critical in acquiring land exactly when the City budget will shrink.

4. Develop a district-wide online notification system to alert stakeholders to new development activity in their neighborhood. Community stakeholders can more effectively participate in shaping development plans that incorporate community and cultural institutions, provide adequate housing types, and preserve the businesses we depend on when we can communicate early and often with developers.

5. Commit to developing policy and funding to support affirmative marketing, right to return, or preference policies in neighborhoods with high displacement risk.

6. Create a comprehensive strategy to help keep low-income or fixed-income single family homeowners in place. Increasing maintenance costs and property taxes make it harder and harder for older homeowners, low-income homeowners, and homeowners of color to afford to stay in their homes, which are one of the only strategies residents have to build wealth and lift their families from poverty. The daily barrage of cash offers for homes, especially homes within existing urban villages or proposed urban villages, may solve the short term need for fast cash but ultimately threaten the stability of low-income homeowners and communities. Strategies should include:

– Develop a program to defer property taxes until sale of property.

– Fund and develop a canvas to inform homeowners of their alternatives and tradeoffs to selling their homes.

– Develop land-use and development strategies to allow homeowners to stay in their homes, but leverage the unused land on their property to both develop new affordable housing AND help homeowners pay property taxes and maintenance costs.

7. Create a temporary City-wide anti-displacement voucher program to help residents stay in place while MHA units are still under construction. This program could complement the City’s Rental Relocation and Inspection Ordinance, by increasing the income qualifications to 80% AMI and extending eligibility to renter or homeowners whose housing costs have increased more than 10% in a given year.

8. Update the Administrative and Finance plan for the Seattle Housing Levy and MHA fund distribution to match Equitable Development Initiative priorities and other community needs like incentivizing family sized units, produce more units at 30% and 40% AMI for families and households who don’t need wraparound services, and prioritize community ownership of land.

9. Develop and implement zoning overlay districts that preserve existing institutions and businesses and the residents who depend on them in neighborhoods with high displacement risk.

Mandatory Housing Affordability in its current form is not enough to keep the workers, families, residents, businesses, and community institutions at risk of displacement in place. We urge you to include these recommendations in the Companion Resolution to the Citywide Rezone and then begin work to implement them through actual legislation and budget deliberations later this year.