This week Seattle City Council took an important, but preliminary step to improve Seattle’s policy tools to build adequate affordable housing. Council plans to raise in-lieu fees developers pay in the downtown area that fund affordable housing in an effort to match fee increases passed for South Lake Union this spring.

Council hopes to encourage developers to build affordable housing in their buildings (sometimes called on-site) by raising the in-lieu fee to a level comparable with the cost of building affordable units.

Developers rarely, if ever, build affordable housing on-site. Because the fees are too low, developers choose to pay the fee and move on, leaving a considerable gap in the available affordable housing stock in the city, particularly downtown. Creating a program that results in actual affordable units included in market rate developments is critical to achieving Seattle’s incentive zoning program goals.

Seattle’s efforts to pass a strong inclusionary housing program are a direct response to four things:

- Market rate development projects increase demand for affordable housing that needs to be mitigated.*

- When local governments create significant value for developers through major infrastructure investments and allowable height increases the public deserves benefits in return, like affordable housing.

- Building affordable housing alongside market-rate housing ensures more people have access to high opportunity neighborhoods and encourages mixed-income, diverse, inclusive communities. This goal is a direct response to historic exclusionary housing practices that have segregated American cities and regions by race and income.

- Creating more housing opportunity in the urban core for the full income mix of Seattle workers means fewer people will need to drive into the city from far-flung suburbs.

Raising the in-lieu fee is a common sense action needed to meet these goals. If the in-lieu fee remains too low, developers will understandably continue to pay a low fee rather than build affordable units in their projects.

Council’s action this week is preliminary. When you consider past research on the question and compare Seattle to other cities, (look for this comparison soon on Sound Progress) the results suggest that the in-lieu fee will still be too low to make on-site construction of affordable units attractive to developers. Over the next six months, City Council and the Mayor’s office will learn from national and local experts in an effort to build a program that results in a significant number affordable units and real inclusion.

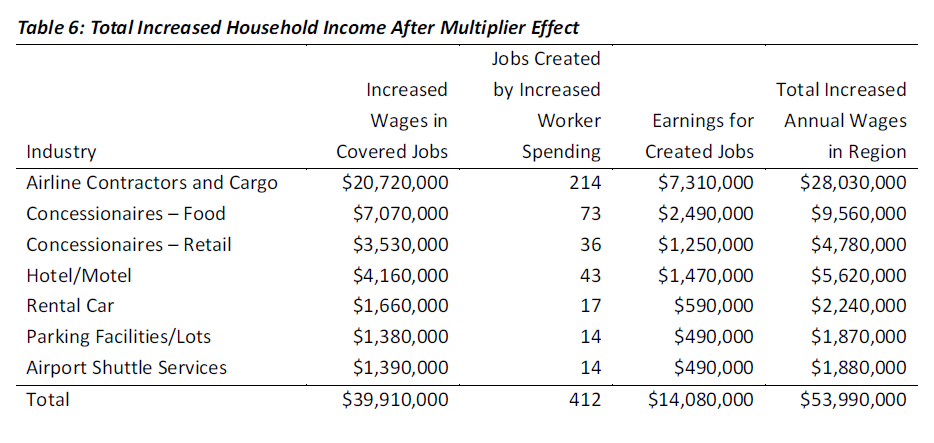

* Upon re-reading this post, I want to clarify this statement: by market rate development, I mean commercial development that fosters new low-wage jobs (20% in the downtown area according to a recent City study), in turn requiring new affordable units it the region.